Our God Helmet experiments employ double-blind conditions and placebo protocols – A Blog by Dr. Michael A. Persinger.

Our God Helmet experiments employ double-blind conditions and placebo protocols – A Blog by Dr. Michael A. Persinger.

Our critics are mistaken when they claim we do not use proper controls. We are committed to the scientific method, especially in laboratory experiments, including subject blindness, experimenter blindness, control groups, and blindness by those who analyze our data.

Question: What are your standard double-blind and placebo controlled protocols?

Answer: Expectancy and confirmation bias are always important variables when human beings are measuring or being measured. Most of our major experiments over the last three decades with the sensed presence were double blind. For a placebo, we use a “sham” or absent magnetic field, which we create by disconnecting the solenoids (magnetic coils) from the signal source. We also exploit all ways and means for ensuring that our subjects are not given any suggestions as to the purpose of the experiment.

Subject Expectations

The subjects volunteered for a relaxation study and were told (via the consent form) they might be exposed to a weak magnetic field. Four to six weeks prior to their participation, the subjects had completed intake questionnaires. Some critics have mistakenly said that our questionnaires (which asked about some spiritual and otherworldly experiences and beliefs) were administered immediately before the experimental sessions, and that this introduced inadvertent suggestions. In fact, our standard procedure is to separate the questionnaires from the sessions by an average of a month. They are eventually invited to participate in a “Relaxation Experiment”, so they are unaware that the questionnaires given previously have any relation to the experiment. The subjects are kept in the experimentally blind condition. They are not influenced by expectations when coming into our lab. The lab itself looks like a busy workplace, and is not decorated with religious or spiritual images.

Blind Protocols

The experimenter, usually an undergraduate or graduate student, who runs the experiment is not aware of the true hypothesis or mechanism.

One summary of our work with the sensed presence is our publication: “The sensed presence within experimental settings: implications for the male and female concept of self” The Journal of Psychology, 2003, 137, 5-16.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12661700/

Here is a very brief summary of that experiment, with its 50 male and 50 female subjects.

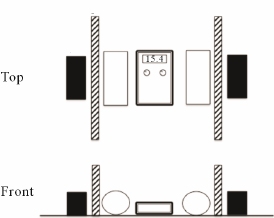

In this study, we used a signal derived from burst-firing in the amygdala, applying it over the temporal lobes via a set of four solenoids over each temporal lobe. We rotated the signal by turning them on and off in sequence. All of this was built into the hardware, built by Stanley Koren (The God Helmet) or coded into the software that drives it, written by Stanley Koren. We applied the signal for 10 minutes, gave it a 5 minute break, and applied it for another 10 minutes. This was done to avoid habituation.

We observed double-blind conditions, as one can see in the research report:

“All participants were tested by experimenters who were not familiar with the purpose of the experiment.”

“The participants were told that the experiment was concerned with relaxation.”

Note that in some experiments, subjects were told that the experiment concerned memory. The relaxation and memory suggestions kept the subject in an experimentally blind condition.

The experimenter ran different patterns of magnetic fields created by Professor Stan Koren and me. Once the results were collected they were analyzed routinely by SPSS (statistical analysis) software.

Women reported more frequent experiences of a sensed presence than men did , and men were more likely than women to consider these experiences as “intrusions” from extrapersonal or ego-alien sources. Both effects were predicted by one of our hypotheses (vectoral hemisphericity) and the known neurologically-based cognitive differences between right-handed men and right-handed women.

The point here is that we do in fact use double-blind conditions, and claims to the contrary are simply not true. Other examples, referenced here, include Richards (1992) Persinger (1994), Healey (1996), Persinger (1999), Persinger, (2002) Booth (2005), Tiller (2002), Corradini, (2014). I have emphasized this in my response to Pehr Granqvist (who made critical technical errors with our equipment, and alleged that our results were due to improper blinding and subject suggestibility), as follows:

“In all of our major studies, involving more than 400 subjects, during the last 20 years the subjects were not aware of their experimental conditions and experimenters were not familiar with the hypotheses being tested or both were not aware of the experimental condition. Subjects had volunteered for “memory” or “relaxation” studies and were randomly or serially allocated to conditions. The “sensed presence” issue was never discussed. The person generating the hypothesis never had direct contact with the subjects.” (Persinger, 2005)

Regrettably, online critics often fail to include this critical reply to Dr. Granqvist.

Let me underscore that we have applied double-blind protocols in our “sensed presence” studies, (to make the differences in stimulation explicit) by quoting another of our papers:

“Under double blind conditions, the subjects who were exposed to the burst-firing pattern presented over both hemispheres or the right hemisphere reported more sensed presences than those exposed to the sham-field [control] or to left hemispheric presentations. Subjects in the latter condition reported fewer sensed presences than the sham-field controls. (Booth, 2005 B)”

Here, stimulation of the right hemisphere is compared to both stimulation of the left, and to controls. This method allows greater certainty for our results.

Moreover, we often employ “blind” analysis of EEG and QEEG data, in which the person carrying out the analysis does not know what hypothesis the data is intended to study (Makarec, 1990).

In our rat studies, we also carry out blind analysis of rat brain sections, in which the investigator does not know which brain regions may have been affected by a procedure, or the magnitude of the differences predicted between the rat brains used in the study and those which were not (Fournier, 2012). In rat studies investigating differences in rat behavior following stimulation with magnetic signals, the experimenter observing their behavior is kept blind to the experimental condition (Whissell, 2007, McKay, 2004, Bureau, 1994, Babik, 1992). Our examination of microscope slides from rat subjects and controls is also done under blind conditions (Cook, 1999). We have also carried out similar procedures with worm (planarium – Dugesia sp.) studies (Mulligan, 2012).

” …a total of 10 undergraduate students participated in measuring the worms’ activity; the students were unaware of the experimental conditions, that is, the study was completely “blind”.”

When we analyze the congruence between intuitively-derived narratives from individuals with exceptional cognitive skills and actual information, we use groups of student “raters” who compare the two data sets, and rate the degree of congruence. All raters are “blind” in that they don’t know anything about the circumstances under which the narratives were derived, or the overall purpose of the experiment (Hunter, 2010). We also employed the same technique to assess the accuracy of remote viewing by the artist Ingo Swann using graphic images he sketched during remote viewing sessions, augmented by our “Octopus” apparatus (Persinger, 2002, B). In a related case history, we attempted to interpolate a specific image from a collection of art prints into the dreams of another. The “agent”, who repeatedly viewed a randomly-chosen (based on dice throws) art image, and was the only one who knew which image was being used.

“The interviews were conducted double blind; neither the percipient nor the experimenters knew the identity of the target or the pool of art prints from which the target had been randomly selected.”

The results demonstrated that greater accuracy was associated with lower geomagnetic activity.

Placebo Controlled, Double-Blind Studies.

Our placebo controls are created by using inert electromagnets (solenoids). These are not attached to the signal source. The experimental procedures are identical in all other respects. We also use our placebo fields in conjunction with double-blind conditions in our studies. Here are a few examples:

- Corradini’s (2014) study facilitating declarative memory

- Fournier’s (2012) experiment with prenatal rat hippocampus stimulation

- Mulligan’s (2012) study with planaria.

- Whissell’s (2007) experiment on the interactions of nitric oxide and seven hertz magnetic fields.

- Booth’s (2005) sensed presence study.

- My own study on increased alpha activity from the left hemisphere with stimulation with our burst-firing pattern (Persinger, 1999).

- My study on enhanced hypnotic suggestibility (Persinger, 1996).

- A study that assessed the pleasantness of a long-term potentiation signal (Persinger, 1994).

- A study of coherent responses to Reiki between practitioners and clients (Ventura, 2014)

- An experiment with altered state experiences with circumcerebral magnetic stimulation (Collins, 2013)

- Lowering depression and increasing alpha activity in the frontal lobe. (Corradini, 2013)

Sham fields are also used in our studies with cell cultures (Murugan, 2014 A), water Ph (Murigan, 2014 B), Obesity in rats (St-Pierre, 2014), Suppression of Cancer cells, (Karbowski, 2012), energy storage in water (Gang, 2012), planeria studies (Gang, 2011) and scores of other studies that didn’t use human subjects.

The issue of double blind and placebo control is less important with our modern technology because of the availability of normative (“averages”) for different states, including placebo response states. Comparing the results of our EEG studies to standard normative EEG states allows us to make inferences that would have required baseline (control) readings just a few years ago (Congedo, 2010).

During the last 5 years, quantitative electroencephalographic measurements by computer and the algorithms to compute distributions of power within the volume of the brain for different frequency bands have become available, and these have revealed that different patterns of fields, delivered to different sides of the brain, produce specific patterns regardless if the person knows if a field is presented or not (Saroka, 2013). Placebo effects produce very specific patterns that are not the same as those associated with either the field presentation or the field plus sensed presence effect.

In spite of claims to the contrary, we do use placebo controls and blind experimental conditions. Our emphasis has been on quantifiable data, replication, and blind conditions, wherever possible and appropriate. We remain committed to the scientific method.

I hope this blog will clarify our use of blind conditions, placebo controls and suggestion in our laboratory.

Dr. Michael A. Persinger

Full Professor

Behavioural Neuroscience, Biomolecular Sciences and Human Studies

Departments of Psychology and Biology

Laurentian University,

Sudbury, Ontario, Canada P3E 2C6

Email: mpersinger@laurentian.ca and drpersinger@neurocog.ca

NOTE: This blog is hosted by a colleague.

REFERENCES (NOTE – links open in new windows):

P.M. Richards, S.A. Koren, M.A. Persinger, Experimental stimulation by burst-firing weak magnetic fields over the right temporal lobe may facilitate apprehension in women, Perceptual and Motor Skills 75 (1992) 667–670.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1408634/

Persinger MA, Richards PM, Koren SA. “Differential ratings of pleasantness following right and left hemispheric application of low energy magnetic fields that stimulate long-term potentiation.” International Journal of Neuroscience. 1994 Dec;79(3-4):191-7.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7744561/

Healey F, Persinger MA, Koren SA. “Enhanced hypnotic suggestibility following application of burst-firing magnetic fields over the right temporoparietal lobes: a replication.” International Journal of Neuroscience. 1996 Nov;87(3-4):201-7.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9003980/

Krippner, Stanley, and Persinger, Michael. “Evidence for enhanced congruence between dreams and distant target material during periods of decreased geomagnetic activity.” Journal of Scientific Exploration 10.4 (1996): 487-493.

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.488.9053&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Persinger, M. A. “Increased emergence of alpha activity over the left but not the right temporal lobe within a dark acoustic chamber: differential response of the left but not the right hemisphere to transcerebral magnetic fields.” International Journal of Psychophysiology 34.2 (1999): 163-169.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10576400/

M.A. Persinger, F. Healey, “Experimental facilitation of the sensed presence: possible intercalation between the hemispheres induced by complex magnetic fields”, Journal of . Nervous and Mental Disorders. 190 (2002) 533–541.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12193838/

Booth, J. N., S. A. Koren, and M. A. Persinger. “Increased feelings of the sensed presence and increased geomagnetic activity at the time of the experience during exposures to transcerebral weak complex magnetic fields.” International Journal of Neuroscience 115.7 (2005 A): 1053-1079.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16051550/

Tiller, S.G; Persinger, M.A. , Geophysical variables and behavior: XCVII. “Increased proportions of left-sided sense of presence induced experimentally by right hemispheric application of specific (frequency-modulated) complex magnetic fields”, Perceptual and Motor Skills 94 (2002) 26–28.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11883572/

Persinger, Michael A., Letter to the Editor “A response to Granqvist et al. “Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak magnetic fields” Neuroscience Letters 380 (2005) 346–347

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15862915/

Makarec, Katherine,; Persinger, Michael A. “Electroencephalographic Validation of a Temporal Lobe Signs Inventory in a Normal Population”, Journal of Research in Personality, 24, 323-337 (1990)

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3927256/

Corradini, Paula L. Collins, Mark W. G. Persinger Dr. Michael A. “Facilitation of Declarative Memory and Congruent Brain States by Applications of Weak, Patterned Magnetic Fields: The Future of Memory Access?” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 13; November 2014, 30

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1086.3972&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Neil M. Fournier, Quoc Hao Mach, Paul D. Whissell, Michael A. Persinger “Neurodevelopmental anomalies of the hippocampus in rats exposed to weak intensity complex magnetic fields throughout gestation” International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 30 (2012) 427–433

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22867731/

Whissell, P.D. , Persinger, M.A.; “Developmental effects of perinatal exposure to extremely weak 7 Hz magnetic fields and nitric oxide modulation in the Wistar albino rat” International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 25 (2007) 433–439

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17942265/

McKay, B. E., and M. A. Persinger. “Normal spatial and contextual learning for ketamine-treated rats in the pilocarpine epilepsy model.” Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 78.1 (2004): 111-119.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15159140/

Bureau, Y. R. J., O. Peredery, and M. A. Persinger. “Concordance of quantitative damage within the diencephalon and telencephalon following systemic pilocarpine (380 mg/kg) or lithium (3 mEq/kg)/pilocarpine (30 mg/kg) induced seizures.” Brain Research 648.2 (1994): 265-269.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7922540/

Missaghi, Babik, Pauline M. Richards, and Michael A. Persinger. “Severity of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in rats depends upon the temporal contiguity between limbic seizures and inoculation.” Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 43.4 (1992): 1081-1086.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1475292/

Cook, Lisa L., and M. A. Persinger. “Infiltration of lymphocytes in the limbic brain following stimulation of subclinical cellular immunity and low dosages of lithium and a cholinergic agent.” Toxicology letters 109.1 (1999): 77-85.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10514033/

Mulligan, Bryce P. , Noa Gang, Glenn H. Parker, Michael A. Persinger “Magnetic Field Intensity/Melatonin-Molarity Interactions: Experimental Support with Planarian (Dugesia sp.) Activity for a Resonance-Like Process” Open Journal of Biophysics, 2012, 2, 137-143

https://www.scirp.org/html/4-1850034_24140.htm

Hunter, M.D., Mulligan, B.P., Dotta, B. T., Saroka, K. S., Lavallee, C. F., Koren, S. A., & Persinger, M. A., “Cerebral Dynamics and Discrete Energy Changes in the Personal Physical Environment During Intuitive-Like States and Perceptions” Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research December 2010, Vol. 1, Issue 9, pp. 1179-1197

https://www.academia.edu/download/43381432/Cerebral_Dynamics_and_Discrete_Energy_Ch20160305-23443-qbptl2.pdf

Persinger MA, Roll WG, Tiller SG, Koren SA, Cook CM. “Remote viewing with the artist Ingo Swann: neuropsychological profile, electroencephalographic correlates, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and possible mechanisms.” Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2002(B) Jun;94(3 Pt 1):927-49.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12081299/

Murugan, Nirosha J., Lukasz M. Karbowski, and Michael A. Persinger. “Weak burst-firing magnetic fields that produce analgesia equivalent to morphine do not initiate activation of proliferation pathways in human breast cells in culture.” (2014).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15219761/

Murugan, N. J., L. M. Karbowski, and M. A. Persinger. “Serial pH Increments (~ 20 to 40 Milliseconds) in Water during Exposures to Weak, Physiologically Patterned Magnetic Fields: Implications for Consciousness.” Water 6 (2014): 45-60.

[PDF] researchgate.net

St-Pierre, Linda S., and Michael A. Persinger. “Progressive Obesity in Female Rats from Synergistic Interactions between Drugs and Whole Body Application of Weak, Physiologically Patterned Magnetic Fields.” Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science 2014

https://www.scirp.org/html/3-3900259_47406.htm

Ventura, Anabela C., Kevin S. Saroka, and Michael A. Persinger. “Non-Locality changes in intercerebral theta band coherence between practitioners and subjects during distant Reiki procedures.” Journal of Nonlocality 3.1 (2014).

[PDF] researchgate.net

Corradini, Paula L., and Michael A. Persinger. “Brief Cerebral Applications of Weak, Physiologically-patterned Magnetic Fields Decrease Psychometric Depression and Increase Frontal Beta Activity in Normal Subjects.” Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology 4.5 (2013): 1-6.

[PDF] iomcworld.org

Karbowski, Lukasz M., et al. “Digitized quantitative electroencephalographic patterns applied as magnetic fields inhibit melanoma cell proliferation in culture.” Neuroscience letters 523.2 (2012): 131-134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22750152/

Gang, N., L. S. St-Pierre, and M. A. Persinger. “Water dynamics following treatment by one hour 0.16 Tesla static magnetic fields depend on exposure volume.” Water 3 (2012): 122-131.

Gang, Noa, and Michael A. Persinger. “Planarian activity differences when maintained in water pre-treated with magnetic fields: a nonlinear effect.”Electromagnetic biology and medicine 30.4 (2011): 198-204.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22047458/

Congedo, Marco, et al. “Group independent component analysis of resting state EEG in large normative samples.” International Journal of Psychophysiology78.2 (2010): 89-99.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20598764/

Saroka, Kevin & Persinger MA, “Potential production of Hughlings Jackson’s “parasitic consciousness” by physiologically patterned weak transcerebral magnetic fields: QEEG and source localization” Epilepsy and Behavior, 2013, 28, 395-407

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23872082/